Understanding Mews Arches

One of the characteristic features of a mews is its entrance and in particular its arch. But how typical is this? What variety of arches are there? Why were the arches built, and who do they belong to?

Arches mark out the mews within their location and give them architectural merit. Mews tend to be uniform in architecture and constructed from conventional materials. Few properties are listed and their conservation area status is based on their collective appearance.

Originally, a mews property was built as the modern equivalent of a live/work unit; residential accommodation was built above an area used for trade or commerce. Functional in design, they were simply constructed on more of an equine scale as they were originally occupied by horses and carriages.

The mews acted as service streets, tucked away from the main houses they served, however, many now show themselves to the public as desirable locations for their village-like feel.

In their book ‘The Mews of London’ Barbara Rosen and Wolfgang Zuckermann explained, “…many a mews is hidden from the glance of the casual passer-by and are entered through arches or discrete gateways often set unobtrusively into a building façade.”

The functional requirements of the mews, together with the shape of the site and the constraints determined by the London Building Acts and byelaws, determined the mews design and layout.

The Metropolitan Board of Works was the legislative body responsible for the approval of applications to create or alter many of the mews. They determined the design aspects, such as the width, height, paving construction details, and access to the mews.

There were five designs for the types of entrances designed to hide the mews from passers-by:

1. A NARROW ENTRANCE

Where the entrance narrows at the point of entry to the mews, which were generally wider than their entrances. The Metropolitan Board of Works required the minimum width to be 20 feet which became part of building regulations. This allowed coaches to pass, for example, Montagu Mews South has a splayed shape at the entrance. This simple visual design on the first mews survives from the 18th century.

Generally, gates were not provided, because the Metropolitan Board of Works made it clear they considered the mews to be public spaces and gates would have compromised this.

2. A CHANGE OF DIRECTION

Here the mews are hidden from sight of passers-by around a corner or by using an offset entrance e.g. Burton Mews.

3. AN ENTRANCE UNDER THE ADJACENT BUILDINGS

Typically, the entrance is incorporated into a terrace of houses using what looks like an arch e.g. Frederick Close. Such designs were not favoured by the Metropolitan Board of Works, who strongly opposed this form as an only entrance to the mews. The Metropolitan Board of Works felt that the mews entrance should be open to the sky to improve ventilation. Dating back to 1865, St. George’s Square Mews was refused permission for two entrances until both were made open to the sky.

4. AN ENTRANCE OPEN FROM ABOVE

This may be designed or consequential e.g., Astwood Mews where the arch has been removed.

5. A SEPARATE MEWS ARCH

19th-century fashion originated by the royal architect, John Nash – in the design of the Royal Mews and his work in Regents Park; thereafter seen on the majority of mews in Belgravia and Kensington.

Belgrave Mews West has an odd, but nevertheless listed freestanding arch. It is not connected to the street façade and is now isolated in the middle of the modern federal German Embassy complex where other parts of the mews have succumbed to indifferent modern designs.

Conservation areas now cover much of central London with around 70% of mews included. Only a smattering of mews contain listed buildings, although most with arches are listed. These arches are less prevalent than their iconic image might suggest with less than 10% of the 378 authentic mews (as recorded by Everchangingmews.com), having an arch.

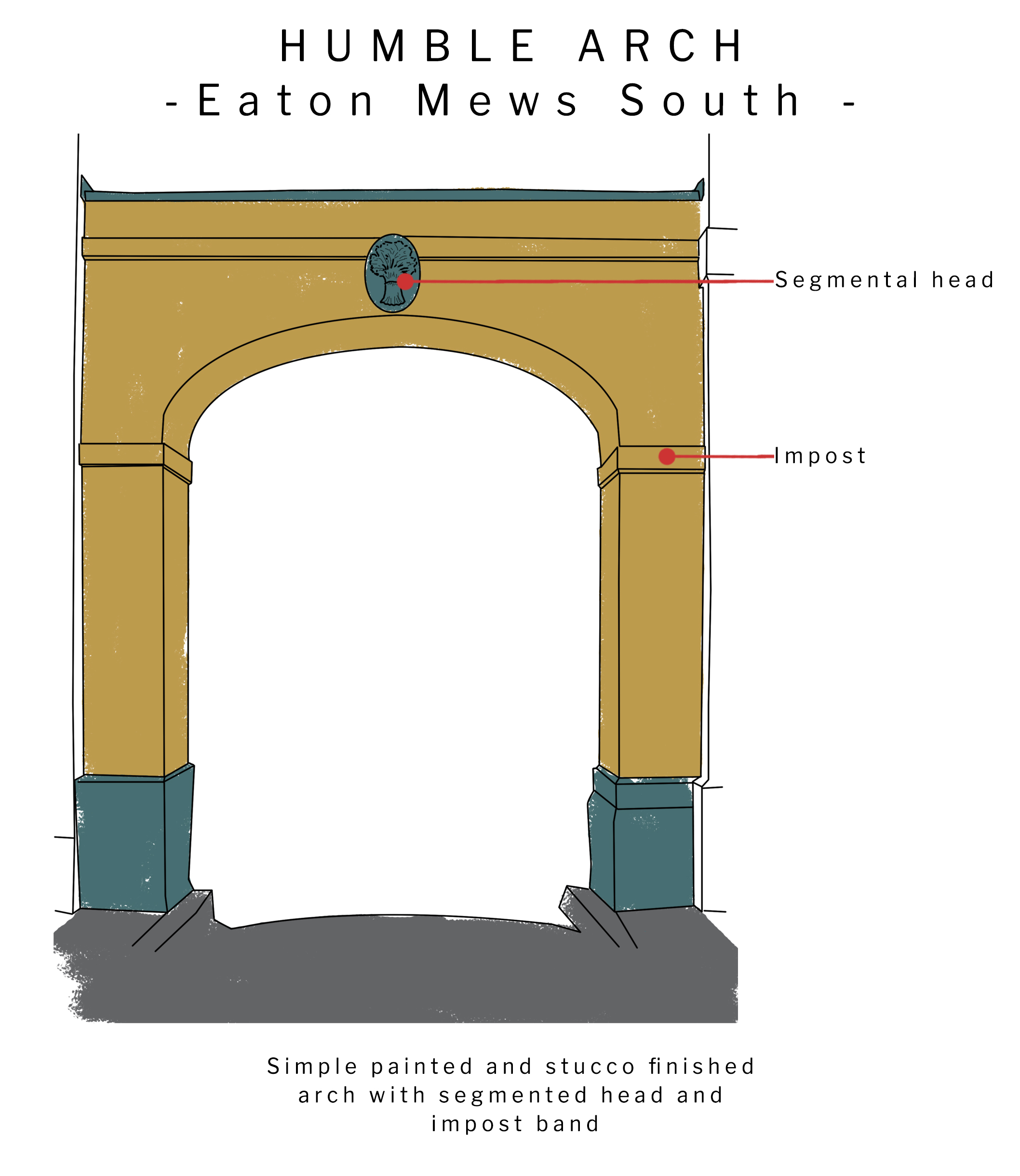

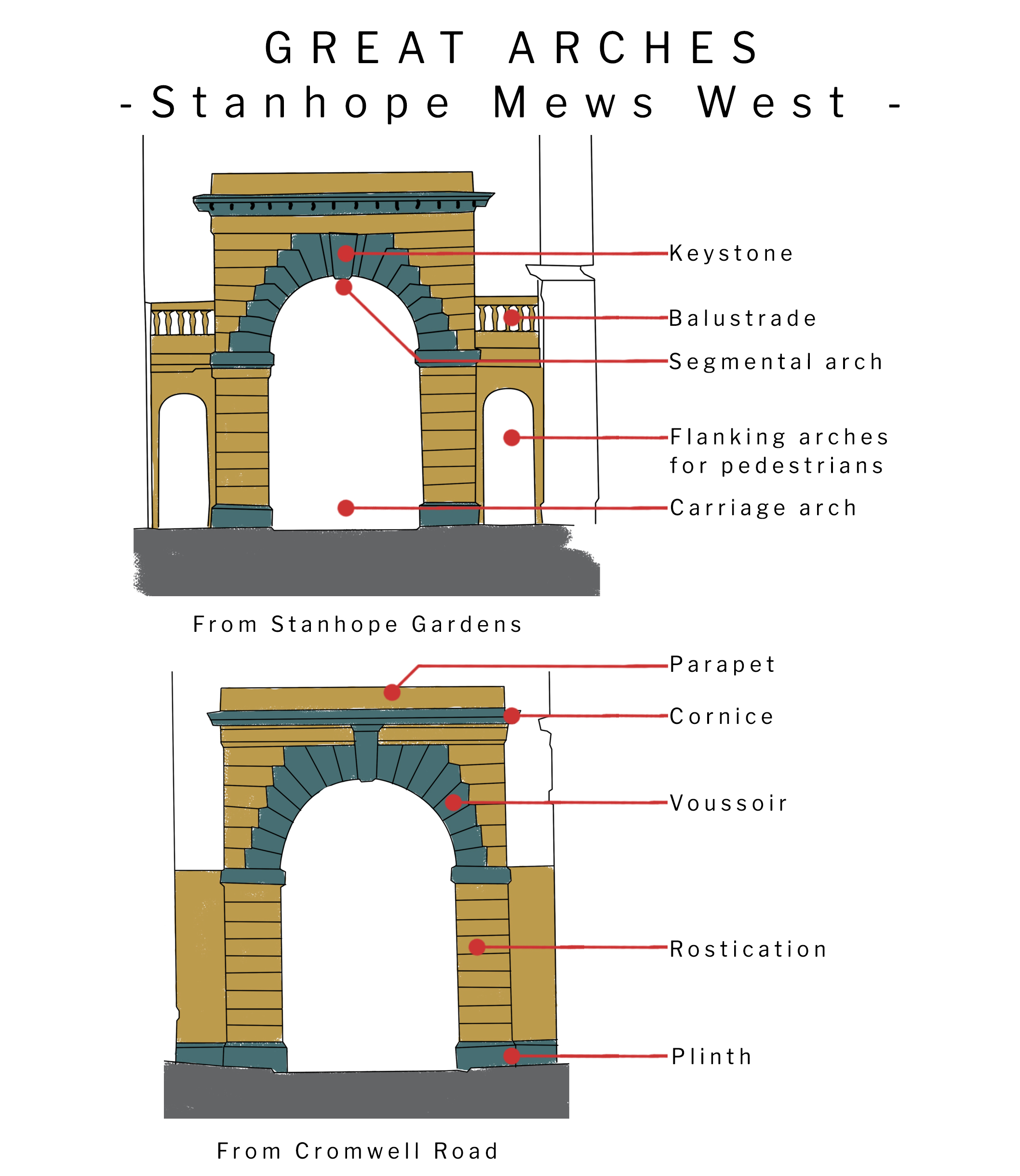

Arches range from simple openings to imposing portals which employ an array of classic motifs.

Here we see the basic classical architectural composition known as an Aedicule i.e., a frame around an opening consisting of two columns supporting the head. Redcliffe Mews has only one arched entrance which is constructed from a simple opening flanked by twin Doric columns supporting an entablature and the pediment, inscribed with the date 1869.

On a slightly grander scale are the arches at Stanhope Mews West. Classical arches dominate the mews on the Grosvenor Estate in Belgravia, the design of many being attributed to Thomas Cubitt. These employ a selection of architectural features such as keystones, rusticated finishes, imposts, cornices, pedestals, parapets, and decorative scrolls. The arches were designed to be unique and at Stanhope Mews West are different at each end of the mews though stylistically complimentary.

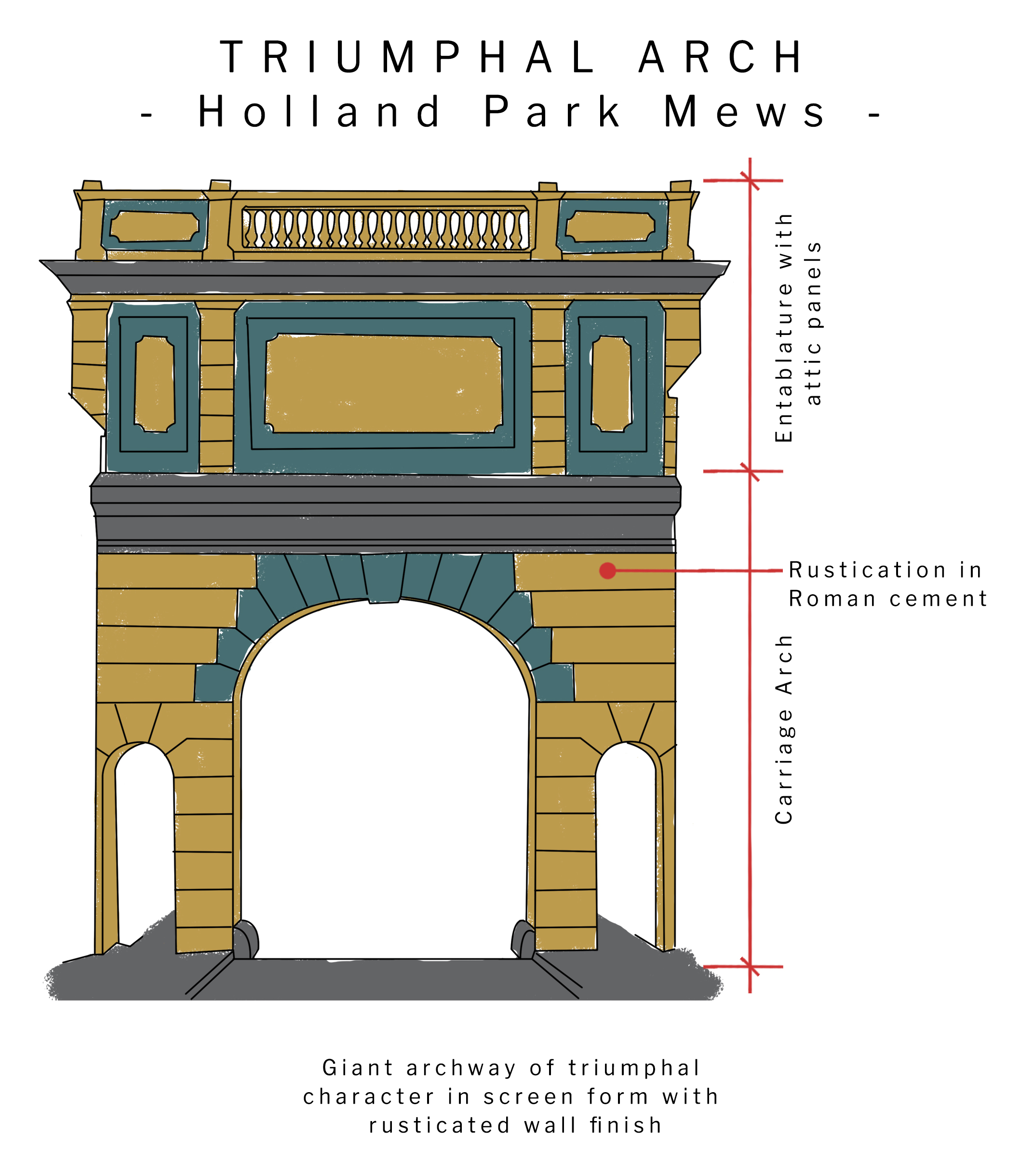

The arch’s primary function is to divide space. Probably the best example of a form of division being the west entrance to Holland Park Mews, which is placed at the bottom of a slope and uses its columns to create three parts – a wide carriage entrance and two narrow pedestrian entrances.

This deliberately echoes the imposing grandeur of the Roman triumphal arch such as Rome’s Arch of Constantine.

Mews arches were designed to maintain the integrity and rhythm of the terrace when it was introduced to the planning of streets and squares – notably Belgrave Square and its surrounding area. Here, the street side of the arches are more ornate and flamboyant than that seen from the mews, which is often left bare.

Today, these qualities attract mews residents, creating a sense of entering an exclusive domain under an imposing arch as if passing through a gatehouse to a private estate.

Classical buildings are based on temples or triumphal arches. From the Temple comes the pediment (the triangular top), and from the triumphal arch comes the particular arrangement of columns and arches.

The triumphal arch is a Roman form and appears on most classical buildings. This comprises the following parts: plinth, bass, engaged columns, keystone, voussoirs, attic story, cornice and decorative panels.

The arch to Queens Gate Place Mews, circa 1855, is a Grade II Listed complex classical design consisting of a large central opening to accommodate a grand carriage with two smaller pedestrian entrances either side. The curved pediments contain an elaborate scrolled motif and entablature are supported by two giant Ionic columns. The elevation has a part rusticated finish.

The ownership of the arches has proven a thorny subject over the years. Ownership of those built into adjacent dwellings, and ones that the estates clearly maintain can be excluded from this ownership mystery, but elsewhere there are independent and freestanding structures without obvious ownership.

This problem was such a concern in 1972, that the town planning committee of Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea affixed a poster to the arches in an attempt to trace their owners. This stated… “This arch is important to the street scene but it is deteriorating due to a lack of maintenance… Who owns this arch?”

Today, the arches seem to have been reclaimed and appear in better repair. Mews and their arches have undergone remarkable changes in the last 200 or so years. It is a testimony to their adaptability that so many are so fully utilised… such is the fascination of the Everchanging Mews.

Further advice about London Mews

This article was written by Martyn John Brown MRICS, MCIOB, MCABE, MARLA, MISVA of Everchanging Mews www.everchangingmews.com and London Mansion Flats Limited www.londonmansionflats.com who is a Chartered Surveyor specializing in Mews and Flats.

Everchanging Mews and London Mansion Flats Limited is owned and run by Martyn John Brown who provides professional surveying advice – for surveys, valuations and Party Wall matters contact info@everchangingmews.com, info@londonmansionflats.com or call Martyn on 0207 419 5033.